Chapter 8 – The Harsh Realities of the ICU

At one point, I was back in the doctor’s garage getting rolled on my side, something about a bowel program? At this point I was really just a consciousness, ever so tenuously attached to a malfunctioning meat suit. Attached to all of those tubes and hoses that were feeding me, breathing for me, and monitoring me, I was just along for the ride. Oh wait, no, I think I can feel my ass hole? Is something… Going in? Is this that spinal cord test again, like the first time I broke my neck? Did I consent to this? My instinct is to recoil and pull away, but I can’t move. Oh man, I think I’m shitting myself. All you can do is let go of the idea that you have control over anything at this point, and you have to just ride it out. The idea of being a completely passive observer, where the only expectation of you is that you stay alive wasn’t the worst all negative, provided it wasn’t going to be permanent. In this case, everyone else involved was just happy that I was finally shitting again; with all of the opioids I had been given, it had been days since anything had come out, something I was blissfully unaware of. It’s hard not to feel shame or embarrassment even though there is absolutely nothing you can do about it, which applies to a multitude of different situations beyond just shitting yourself as a paraplegic or quadriplegic.

The majority of what I felt during my time at the ICU was sheer panic. At that time, everything seemed terrifying, even being left alone for a few minutes felt like playing a high-speed game of Russian roulette; with the silence growing louder and louder with each passing second. Part of this stems from the fact that on numerous occasions, I found myself choking on my own spit or secretions; and while you are laying on your back without the ability to move, turn your head to the side, or breathe forcefully, it felt like the discount version of waterboarding. I say the discount version because, at one point when I was convinced my airway was clogged and I was going to choke to death, my dad calmly pointed out that if I calm down and try to breathe more steadily and deliberately, I can get enough oxygen to not pass out until they could come suction my lungs. One of the most difficult things I had to learn while in the hospital was to relax and trust everything to people who were virtually strangers. The hard truth is, even if things are really bad, it is exceedingly rare that they would tell you, unless they need you to do something; in any case, the anxiety or panic will pretty much never be helpful, and when you are a new high-level quadriplegic [high-level refers to the position up the spine, the higher you go, the less function you have], it’s not like you are even capable of doing anything other than calming the fuck down. It’s rarely pretty, but sometimes you have to stare at the back of your eyelids and just let go, floating into that dark space, while you just concentrate on the most basic survival needs and let Jesus take the wheel… provided that Jesus is a Latino guy with a medical degree.

In terms of waterboarding, I’m pretty sure no matter how much you relax, it doesn’t ever become manageable, which is knowledge I gained over all my years of not being in the military. Not to just casually mention my lungs being suctioned, this procedure, which I would become uncomfortably comfortable with over the next few months, involved taking a catheter and attaching one end to a catch can connected to the vacuum line from the wall and the other end would find its way down my throat and into my lungs. Whoever was doing it would then fish around in my lungs for a bit, trying to suck up as much as possible. Normally, as you breathe, the air is warmed and humidified by the nose and mouth. Without these perks, the lungs become irritated and secretions become thicker and more difficult to clear. This type of suctioning would happen pretty frequently, to the point where eventually I was able to “breathe” while it was happening.

Sometimes I was fully aware of where I was and my situation, while other times I was off in some dreamland, with my brain grasping at little bits of reality and then weaving them into its own little story. A red light here, a mention of Thai food there, and suddenly I was in that Asian high rise; an inclined hospital bed and a screen and I was in an arcade. In one of my more lucid moments, I remember being awake at night in the hospital with my friend Tyler who was keeping me company. She was one of the first people who got to the hospital after my accident and was there throughout, keeping me company and helping with everything. That night, I’m not sure if it was because I actually felt hot or was just desperate to feel something, a theme that would only grow from this point, but I remember desperately asking for an ice bath. There was something particularly relieving about feeling or having those ultracold cloths on, it was like they were physically wiping away the anxiety and panic.

One odd side effect of breaking your neck is that you can lose the ability to sweat, meaning you have no effective way of dissipating heat. In retrospect, a fair amount of my anxiety was probably me just feeling too hot, but not being able to recognize the sensation yet. There are a whole variety of things that I can’t feel or sense directly but that set off reactions within my body that I am able to sense; however, it’s incredibly difficult to reverse engineer the cause of these disparate, ill-defined, and fleeting sensations. Try to imagine all the feelings that are involved when you are too hot, except your brain doesn’t register any of it as “hot,” you are just suddenly an ever-shifting combination of uncomfortable, anxious, exhausted, irritated, etc. This would be the beginning of a long series of discoveries on my body’s inability to regulate temperature, and the particular sensations and indications I would get that my body temperature was leaving the ideal range. But more on this later.

I had a number of visitors who came and saw me in the ICU. To start, I wouldn’t really call Tyler a visitor; she was there from the start, and was there for hours helping with everything… The best way I could describe it is to say that if someone is there with you and the doctor says they are taking you for some medical procedure, they typically tell visitors to leave, and allow a different group of people to be waiting for you when you come out. That’s not to say that I appreciated the visitors any less. It was good to see friends and get little updates about the outside world. I can’t speak for everyone, but if you’re dealing with someone who is antisocial by choice, it’s okay to show up to show that you care and then leave. I appreciated the visits, but also quietly appreciated the brevity of the visits. Besides, most people were clearly uncomfortable, which is totally understandable

My friend Alex and his girlfriend were actually the first two at the hospital, he must’ve been the only person I could even think to contact who might be able to get a hold of my family. I’m pretty sure he was the one who contacted Tyler. Even though my memory is generally not the strongest and that time was particularly confusing, I still remember all of those visits. While I was in the ICU, and all throughout my recovery, the outside world just kind of melted away. Things that weren’t directly in front of me were dropped lower and lower on the priority list. Not because of some conscious effort but because I simply had too much to process. I imagine it’s similar to a baby with their lack of object permanence, except they probably don’t feel guilty for all the neglected relationships and friendships. However, having visitors was always a mixed bag; it was great to see people and get the distraction, but it also came with the anxiety of not wanting to shit myself in front of them (something which was beyond my control, aside from deciding not to see them). Also, there is something particularly sad or painful about seeing the pity on their faces. It also seems like it’s something next to impossible to hide; it’s on their face, in their voice, in their body language… Maybe I just imagined it all? Not likely, I’m sure if I saw my own reaction as I look back on the pictures from when I was in the hospital, I would recognize that same sense of pity. And why not? It was a pitiful sight.

Previously I wrote about experiencing diet waterboarding, as it turns out, I also remember very intense and clear flashes from an experience that could only be described as medical grade waterboarding. I remember hearing the description of what was going to happen and having a slight sense of panic, “you going to do what? Get the fuck out of here… oh shit, oh god… errrr, fuck… ok, no choice, here we go?” For whatever reason, I demanded that my sister record the experience on video; an idea the medical staff were, justifiably, not gung-ho about. They prepped my sister on what was going to happen, and instructed her to, by no means, intervene at any point, regardless of how bad things looked. Which seems like a fair warning given the nature of the procedure.

They were essentially going to perform a lung lavage to clear the secretions that were building up in my lungs due to the pneumonia I contracted between the two surgeries on my neck. To do this they would inject saline into one lung to break up the secretions and then suction it out with the help of a bronchoscope, think tiny camera on the end of a 2 ft long hot dog, sans bun of course. As you can imagine, alternating between having salt water sprayed in your lungs and having a 2 ft long hot dog camera/ vacuum shoved down your throat and into your lungs is… well, brutal. Going back and watching the video, there is a point during the procedure where my eyes open wide and I begin to struggle a bit more, I’m fairly certain this corresponds to one of the flashes of memory I have. It seems clear that I’m more awake than I am supposed to be when the doctor asks if they’ve given me the maximum amount of fentanyl already. And yep, had the maximum but the procedure was going to continue; a situation which caused visible guilt and empathy on the faces of the doctor and nurse... I still struggle to not cry thinking about the procedure. I have been told that I was definitely not supposed to remember any part of the experience, and given how poor my memory is, it seems odd that my brain would just say, “nah, that’s a memory I’ll hold on to forever!”

When tardigrade go into their cryptobiotic tun state, they drop their metabolism to 0.01% of normal and reduce their water content to 1%, which they accomplish with the help of specialized proteins [intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), tardigrade specific proteins (TDPs), and a damage suppressor protein (dsupp)]. In that tun state, their tiny little brains are shut off, meaning they don’t register the abuse they endure in that time. All of that is a complicated way of saying, that was a moment I could have been more of a tardigrade, in a literal sense.

On the opposite side of things, you would think that getting to go outside would be a positive experience; and it definitely was nice soaking in the sun, feeling the warm breeze scented by the autumn grass, and seeing the mountains again. As cliché as it all sounds, being out there did make it feel like it was easier to breathe, “feel” being the operative word, as my actual blood oxygen saturation levels were probably steadily declining… 93, 92, 90, 88... It’s an odd dichotomy to have a place where you want to be so bad but to feel like that place is steadily draining your life force. It felt reminiscent of an old piece of electronics, where you would unplug it from the wall and take it outside and you just watch as the battery slowly drains away before you have to go back inside and plug it in. After only a few short minutes, it was time to plug Kenji back in. In any case, there was also probably something to being able to see the outside world but to know that I was never going to interact with it in the same way again that made me want to go back inside after a while.

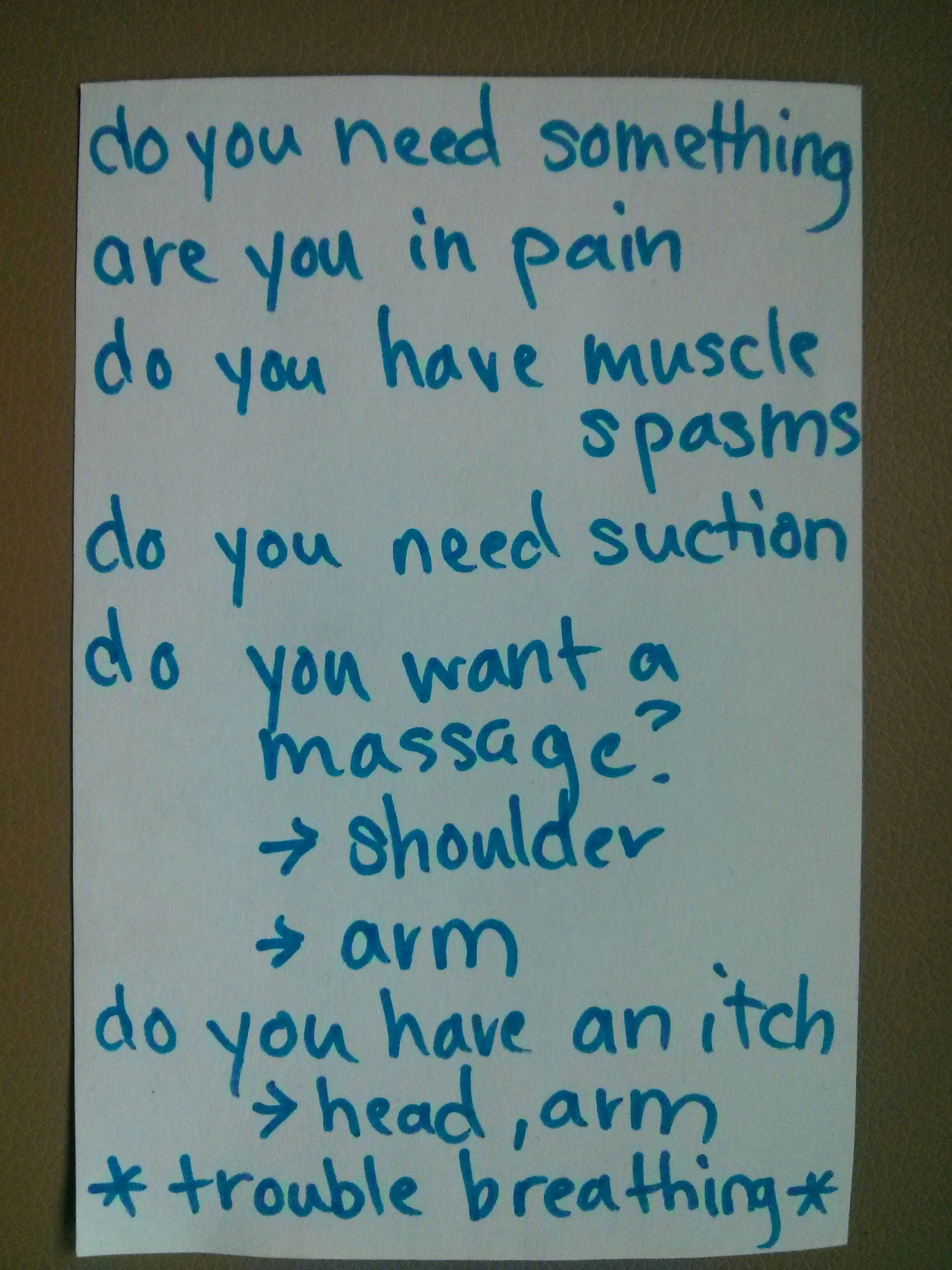

Even when I wanted to do something like go back inside, I wasn’t really able to communicate any of it. Because the tracheotomy is located below the vocal cords and a cuff is inflated to not let air past, air couldn’t pass over the vocal cords to vibrate them, meaning I was unable to speak. Wouldn’t you know, somebody thought of that issue and created what’s called the speaking valve. These speaking valves are simple mechanical one-way air valves which are placed over the tracheotomy hole after deflating the cuff. They allow you to inhale through the valve, but stop the air from going back out when you exhale, which directs the air over the vocal cords allowing you to speak… at least, that is how they were supposed to function. My first experience with one of these valves was during a PT or OT session where, with an abundance of assistance, I was sitting up in the bed, which is a position with a fairly definitive timeline, much like being outside, I was unplugged from the wall again. When my therapist explained what the valve was and how it worked, I was pretty excited to be able to speak again and communicate things like “oh hey, my head itches like crazy, please scratch it,” rather than just sitting there hoping somebody randomly guesses that your head itches. *Extracurricular activity - next time your face or head itches, don’t do anything about it, is it going away? Is it getting better? Will it ever get better? *

Anyway, back to the speaking valve… She placed the speaking valve on my tracheostomy tube, I inhaled, preparing to finally speak again. She instructed me to try a hum, it seemed like a foregone conclusion that I would be able to just speak like normal… “um, Ma’am, I think you underestimate me.” Oh how wrong I was, I suddenly realized I couldn’t exhale, I didn’t have the force from any of the muscles in my torso to push the air out. Also, given that I had just inhaled, inhaling again wasn’t really an option. Had I not experienced the myriad of different ways of not being able to breathe, the panic would have been much worse, but the sharp drop from thinking I was going to speak to knowing I can’t breathe still set off those panic bells. It wasn’t meant to happen that day, they said they would try again, but I’m pretty sure I refused all subsequent attempts while at the ICU.

I remember overhearing some of the staff talk to my family and telling them about Craig Hospital in Denver. Nothing they were saying was really registering and I wasn’t putting forth the mental effort to try to understand. A while later, a woman arrived who was the patient intake coordinator, she sat down and explained what Craig Hospital was and why it might be a good fit for my rehabilitation. She brought a brochure with her that had pictures of the hospital campus, former patients who had recovered, and other random information about the hospital. I remember having mixed feelings about seeing people who had recovered. On one hand, it offered that bit of hope that you might also make this dramatic recovery. On the other hand, people love to show off those who made a full recovery and look at the rest of us like we're just not recovered enough. My doctors had given me a very realistic picture of what had happened to my neck and how that was possibly going to play out. I was well aware that I was likely never going to walk again, but also knew that I would only really find out over time. Throughout my entire experience, I don’t recall anyone ever saying “you’re never going to walk again” or “you will walk again,” which is honesty something that I, personally, greatly appreciated.

It was clear that Craig Hospital represented my best chance to recover as much as possible and make the best use of what ended up coming back. Something about the brochure made it seem like Craig Hospital had a ‘community college with dorms’ vibe. The schedule sounded pretty aggressive in terms of what time you had to wake up, eat breakfast, and then start therapy and classes. It’s funny that something like waking up early could almost deter me from the rehab that might help me walk again. Obviously, my family had done a ton of research and basically the entire hospital staff recommended Craig Hospital; however, for me, it was as if I chose what college to go to while blackout drunk, based on a single brochure.

After the first of the two surgeries, I had a feeding tube running up my nose, down my throat, and into my stomach. I was too out of it to really be paying attention to what delectable slurry was going in there or with what frequency, but I do remember the sensation of having a tube permanently taped to my face, which, as you can imagine, was rather unpleasant. At some point it was decided that it was time for a more long-term solution before I transferred to Craig Hospital, and given that I wouldn’t be able to eat or drink anything as long as I had the trach in, this meant surgically placing a feeding tube straight through my abdomen to my stomach. I’m not sure if this was even a thing that I needed to decide or if it was just a given that it was happening but I definitely didn’t have any objections.

If I remember correctly, my surgeon was an Asian woman, in fact, I feel like the majority of people involved in the surgery were women. I only mention this because I have always felt more comfortable with medical professionals who are not straight, white, males. Part of this comes from a general discomfort with being around groups of guys. The chameleon nature of my personality meant that I would try to blend in, usually overcompensating, and it was extremely uncomfortable. That’s not to say that I am any different than any of the guys I’m talking about, I just mean that when I am in a group of guys my personality shades in a direction that makes me uncomfortable, in an attempt to seem normal. I honestly believe that I am capable of significant empathy and “good,” as well as [shameful/ embarrassing/ horrible/ shocking/ dreadful] depravity and “evil.” It’s probably why I’m almost always confused when people say “I just don’t understand how they could…” in response to some terrible incident. I might think something is fucked up, but I typically still understand the motivations involved… though, I guess that is all dependent on how you define “understand” in this context.

[Now, for a little tangent,] I concede, the real champions of blending in are cuttlefish, which use 3 types of cells to change color: Pigmented Chromatophores, little elastic sacs called cytoelastic saccule, which are filled with pigment granules. 18 - 30 radial muscles are attached to each chromatophore and are able to change the size and shape in order to control translucency, opacity, and reflectivity. This allows for active conscious control of color displays [yellow/orange (the uppermost layer), red, and brown/black (the deepest layer)].; Iridophores, chromatophores that utilize structural color to produce iridescent colors. Rather than producing color by selectively absorbing certain wavelengths of light, iridophores use stacks of plates of guanine based crystalline chemochromes to create a diffraction grating. The orientation of the stack, the thickness and tilt of the plates, the spacing between each plate, as well as the number of plates in each stack determine the perceived color. The iridophores are also able to polarize the reflected light, which they use for mating displays and possibly communication. Cephalopods have a rhabdomeric visual system, meaning they are visually sensitive to polarized light; and Leucophores, which are also structural reflectors but they utilize a guanine based crystalline purines to reflect light. However, their organized crystal structure works to reduce diffraction; this means that the leucophores act more like mirrors, reflecting the color of the light source. Towards the surface, they reflect mostly white light, but as they travel deeper and more frequencies of light are filtered out, that shifts toward the red end of the spectrum. Cuttlefish are also able to change the texture of their skin and are much smarter [research suggests they can count] and more interesting than chameleons. It’s all a bit ironic how complex their color display is, given that they are actually colorblind... wait… what the fuck was I talking about? Oh yeah, the other part of my comfort in having an Asian female surgeon comes from knowing that she probably had to work harder, be smarter, and do better than her straight white male counterparts to get to where she is.

I remember being rolled into the operating room, at this point a familiar feeling, and watching as the “dentist office spotlight” slid overhead and dominated the view. The anesthesiologist walked me through the procedure for adding the anesthetic to my IV to put me to sleep. Injection went in. Counting back, 10, 9, 8, 7, …, 6, … 5, …, 4, 3, 2, 1… wait, was I supposed to make it to 1? A few surprised looks and a few giggles. OK… Let’s try that again, Injection went in. 10, 9, 8, 7, …, 6, … 5, …, 4, 3, 2, 1… Big grin on my face… ok, I know I was supposed to go out on that one. I’m not sure how many times we tried but at some point, I asked if I could just stay awake and get local anesthetic, which honestly made me giggle; the thought of medically numbing an area I already can’t feel. After I explained that I had been awake for a previous knee surgery that I was allowed to watch, and a few “you sure?” questions from concerned faces, they decided to let me stay awake. I recently read an article that strongly suggested marijuana users tell their surgeons because a study indicated that they may require up to 10x the amount of anesthetic to “stay asleep” during the procedure; that… is a lot… but could explain a few things.

Nothing of note really happened during the surgery, I couldn’t watch directly this time so it was mostly small talk. Had they not been so nice, I probably would have quickly regretted asking to stay awake. I’m not entirely sure why but the experience always makes me smile when I think about it. I much prefer the entertainment and education of being awake during the surgery to just waking up and fighting through the fog with everything being done.

Me, Sans nasal feeding tube!

I guess I should mention that part of the reason for being in the ICU for as long as I had been was because I had to have two surgeries to fuse my spine; one going in through the back, leaving a long scar down the back of my neck, and one going in through the front, leaving a much smaller scar on my throat, just below my Adam’s apple. However, in between the two surgeries I managed to catch pneumonia, which meant they would have to wait until it cleared before they could continue. Now, without the ability to sweat and control my body temperature, the swings between freezing and burning felt aggressive. Additionally, the combination of a complete lack of use of any of the muscles in my torso and the tubes in my throat made clearing anything in my lungs next to impossible without significant help. Pneumonia, being a lung infection, causes inflammation in the lungs, fever, chills, and crucially, causes the air sacs to fill with liquid or pus. This usually causes a cough, but when I went to cough, I would simply get a tiny breath outward that was entirely ineffective at helping me stay alive.

A picture from earlier, showing the scar and trach.

There were two main methods that I remember being used on a consistent basis to get me to clear the buildup in my lungs. The first was the catheter snaking down the hole in my trach and into my lungs that I mentioned before. The other, somehow, felt more aggressive than the suction and is called a quad cough and involves someone timing a forceful push on your abdomen to simulate the actions of the abs and diaphragm to squeeze a bunch of air out quickly. It rarely worked on the first try, meaning you had the pleasure of having someone rapidly rearrange your internal organs multiple times in short succession while you attempt to time a cough to clear your lungs so you can breathe again. The methods both relied on the secretions in your lungs to be fluid enough to be removed, which was not always the case. When things were really bad, they would do the aforementioned lung lavage but in between those times, one of the therapies they used was chest physical therapy. For me, this meant I was put on a special bed that vibrated rather violently to use percussion to shake the secretions in the lungs loose. When you picture your neck as a bunch of random bits loosely held together, the shaking was not only uncomfortable but also turned the anxiety knob up a notch. To make things worse, because this was all in service of clearing that crap from your lungs, the whole thing comes with the understanding that they were also going to suction your lungs afterwards; so, the unpleasant experience was always just the appetizer for an even more unpleasant experience.

When I finally stabilized after the surgeries and all the preparations were complete, it was time to transport to Craig Hospital. I’m not sure if they were just the only ones available or if it’s standard for the transport, but I was getting transported by the helicopter paramedics, which I found endlessly fascinating. Instead of wearing the normal paramedics uniform, I remember they were wearing dark blue jumpsuits with orange lettering with a military style flag patch on the arm. Across their backs, orange letters spelled out “fight for life.” They transferred me to their super fancy yellow stretcher which had a little platform over my feet for all the monitoring equipment and rolled me outside to the kind of old school looking dulled orange ambulance. On the way out I remember them showing the items that they had taken and held for me when I came in, including a couple beers and a 1.5-foot-long machete, which I used to carry with me everywhere. It was a black machete strapped to the side of a black hiking backpack, it seemed less weird than it does now that I’m writing it out. Once we were in the ambulance, I remember starting to play that little game where I looked out the window and tried to guess where we were. The only problem, we were starting in an unfamiliar place and going somewhere I had never been. I basically had no idea where we were at any point, and to be honest it wouldn’t be until months later that I had a sense of where I was geographically. For me, in situations like this, where something extreme is happening locally, my world shrinks and everything outside gets excluded from processing. On one hand this definitely helps isolate issues and helps you hyper focus; however, in addition to ignoring people, places, and events outside of that bubble, it is severely disorienting when trying to leave and re-expand that bubble to include the entire world again. I don’t remember a whole lot from the ride, probably because I didn’t recognize anything beyond, “oh hey, that’s a tree.” It felt like a much milder version of that kidnapping victim who is locked in a trunk and is trying to figure out where they are based on the subtle clues: 20 minutes on the highway, exited the highway, turned right, smells like fresh asphalt, 5 min straight… OK, by my calculation, we are… still in Colorado? Maybe? Once we got to Craig Hospital, it was straight inside and up to the room.